Public health crises have always been accompanied by waves of public reaction, ranging from calm caution to intense fear. The outbreak of monkeypox in recent years is no exception. While it is not a new disease—it was first identified in 1958—its sudden appearance in countries where it was previously rare has captured global attention. Alongside the scientific and medical challenges of containing the virus, governments and health professionals must also grapple with the public fear that surrounds it.

This article explores what monkeypox is, why it has generated public concern, how fear can shape our responses, and the importance of balanced communication during health emergencies.

1. Understanding Monkeypox

Monkeypox is a viral zoonotic disease, meaning it can spread between animals and humans. It is caused by the monkeypox virus, which belongs to the same family of viruses as smallpox but generally causes milder illness.

Symptoms

Monkeypox symptoms can develop within 5 to 21 days after exposure and often include:

Fever

Headache

Muscle aches

Swollen lymph nodes

Rash that progresses from flat lesions to fluid-filled blisters, eventually crusting over

The illness typically lasts 2 to 4 weeks. While most people recover without serious complications, severe cases can occur, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems, children, and those with other health conditions.

Transmission

Monkeypox spreads through:

Close physical contact with infected individuals

Contact with contaminated objects like bedding or clothing

Respiratory droplets during prolonged face-to-face interaction

In rare cases, from animals to humans via bites, scratches, or consumption of undercooked meat from infected animals

2. Why Monkeypox Sparks Public Fear

Fear during outbreaks often goes beyond the actual threat level posed by the disease. Several factors contribute to heightened anxiety around monkeypox.

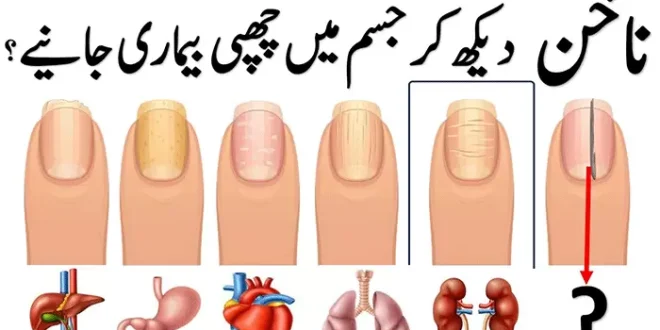

a. Visual Symptoms

Unlike some viral infections, monkeypox produces visible skin lesions. Images of the rash shared in media reports can be alarming, creating a strong emotional reaction.

b. Association with Smallpox

Since monkeypox belongs to the same virus family as smallpox—a historically deadly disease—it triggers deep-seated fears, even though it is far less lethal.

c. Unfamiliarity

Until recently, monkeypox was largely confined to parts of Central and West Africa. The sudden rise in cases in North America, Europe, and other regions made it seem mysterious and unpredictable.

d. Rapid News Spread

The speed of modern news and social media amplifies fear. While rapid communication helps raise awareness, it can also spread misinformation and create panic.

e. Outbreak Timing

Emerging in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, monkeypox hit a global population already sensitized to infectious disease threats, making people more reactive.

3. The Role of Misinformation

Fear is often worsened by inaccurate or misleading information. In the case of monkeypox:

Some social media posts exaggerated its lethality.

Others falsely linked it to unrelated health issues or conspiracy theories.

Misunderstandings about how it spreads led some people to believe casual contact in public spaces was highly dangerous.

These narratives can cause unnecessary fear and even stigmatization of certain communities.

4. The Public Health Response

Managing monkeypox involves both medical and communication strategies.

a. Containment Measures

Isolating infected individuals

Tracing and monitoring contacts

Using vaccines, particularly the smallpox vaccine, which offers cross-protection

Promoting hygiene and safe interaction practices

b. Clear Communication

Health authorities must provide accurate, accessible information to:

Explain how the disease spreads

Reassure the public about relative risks

Counter misinformation promptly

5. Balancing Awareness and Fear

Effective public health communication walks a fine line between:

Understating the risks, which may lead to complacency

Overstating the risks, which may cause panic

A balanced approach emphasizes:

The real but manageable nature of the disease

Practical steps individuals can take to reduce risk

The importance of seeking reliable information sources

6. The Social Impact of Fear

Public fear during health crises can have unintended social consequences:

Stigma: Individuals with monkeypox symptoms may face discrimination, especially if the disease becomes linked with certain demographics.

Avoidance of healthcare: Fear of being judged or quarantined might stop people from seeking medical care.

Economic effects: Fear can reduce travel, tourism, and public events, even if the actual risk is low.

7. Lessons from COVID-19

The global experience with COVID-19 provides valuable insights into managing fear during outbreaks:

Transparency builds trust; hiding information breeds suspicion.

Community engagement helps tailor responses to cultural and social contexts.

Misinformation countermeasures are as important as medical interventions.

8. Reducing Public Fear While Maintaining Vigilance

Practical ways to address fear without downplaying risk include:

Sharing clear explanations about disease severity and transmission

Highlighting recovery rates alongside case numbers

Offering guidance for self-protection rather than focusing only on restrictions

Providing mental health support during outbreaks

9. Long-Term Considerations

Monkeypox is unlikely to disappear completely, meaning:

Health systems may need to incorporate it into ongoing surveillance programs.

Vaccination strategies may be targeted for at-risk populations.

Public health campaigns will need to sustain awareness without creating alarm fatigue.

10. Final Thoughts

Monkeypox is a reminder that infectious diseases can emerge or reemerge in unexpected places. While the medical threat of monkeypox is significant, the social threat posed by fear and misinformation can be just as damaging.

A well-informed public is better equipped to respond calmly and effectively. By providing accurate information, addressing myths, and promoting practical prevention measures, health authorities can reduce unnecessary fear and focus attention on the real steps needed to protect communities.

Public fear in the face of disease is a natural human response—but it should never be the driving force behind public health policy. When science, communication, and community trust work together, outbreaks can be managed without letting fear take control